What Is ‘Fridging’? The Gross Origins & True Meaning Of A Huge Hollywood Problem

When it comes to movies, TV shows, and comic books, tropes make the world go round. Who could ever fault a good enemies-to-lovers arc, a classic origin story, or a surly mentor character? Especially in genre fiction like superhero stories, fantasy, and science fiction, tropes function as markers for the audience — indicators that yes, this is the kind of story you think it is. But some tropes, like the infamous “woman in the refrigerator,” are only harmful.

You likely know this fictional trend by the shortened term “fridging,” or you may not have heard of it at all. In essence, fridging is when a character (typically a supporting female love interest) is killed off in order to give the protagonist (typically male) a motivating force or initiating event with which to start their own story. While fridging can occur with non-female characters, especially queer characters, it’s predominantly recognized as a trope for how women are written. Often, the characters in question don’t serve any real purpose in the story other than to eventually be murdered, assaulted, or otherwise tormented. They serve as fuel for the leading men, and nothing more.

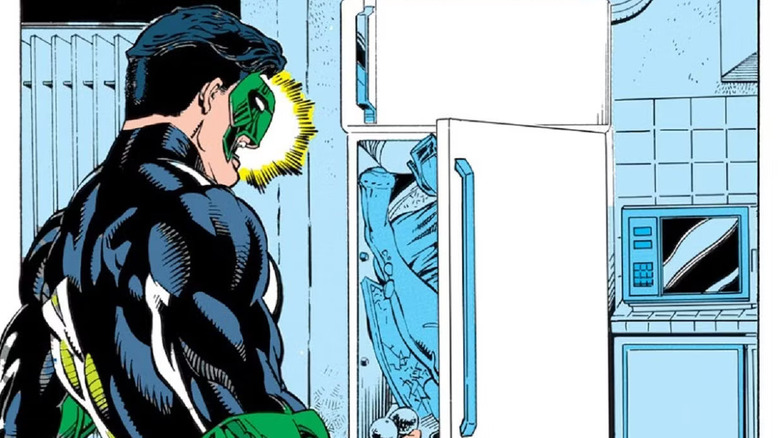

Though the mechanics of fridging were present in fiction long before the phenomenon had a catchy name, this trope was first identified in the late ’90s by eventual comic book writer Gail Simone. The “women in refrigerators” title was a reference to a dark piece of Green Lantern history from 1994.

The comic book origins of fridging explained

In 1999, noted comic writer Gail Simone noticed a pattern in her medium. Time and time again, she saw female characters killed off, brutalized, or stripped of their powers, all seemingly in the interest of someone else’s story. She built a list of characters who befell this fate and made a website, WomenInRefrigerators.com, to bring the matter to the people. She took the title from “Green Lantern” Volume 3, #54, in which the villain Major Force kills Green Lantern’s girlfriend, Alex DeWitt, and crams her body into the refrigerator for him to find.

“These are superheroines who have been either depowered, raped, or cut up and stuck in the refrigerator,” Simone wrote on the site. “I know I missed a bunch. Some have been revived, even improved — although the question remains as to why they were thrown in the wood chipper in the first place.”

Ron Marz, the writer of the infamous “Green Lantern” comic, wrote his own response that Simone published on the website. In it, he acknowledged that the trends of comics at the time prioritized only male readers, often to the medium’s detriment. “I think the obvious point here is that female characters, in general, have a rougher time of it,” Marz wrote. “… Publishers are unfortunately more concerned with survival than with sensitivity to women. And that’s a shame. If we want to save our industry, maybe we should stop ignoring half the population as possible readers.”

Fridging is still a big problem today

Though Simone began by identifying the problem of fridging in comics, it’s equally prevalent in film and television, and it’s still a major issue today. The Marvel Cinematic Universe, for instance, has received frequent criticism for fridging characters like Black Widow in “Avengers: Endgame,” Maria Hill in “Secret Invasion,” and Thor’s mother Frigga in “Thor: The Dark World,” just to name a few. Fridging also occurs in a number of Christopher Nolan movies, including “The Prestige,” “Inception,” and “The Dark Knight” — films where the cast is predominantly male.

On television, you can point to characters like Tara in “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” who’s killed by a random bullet after seasons of leading the series’ prominent queer relationship. Jane in “Breaking Bad” is another good example, as she really exists in the story only to give Jesse another tragedy and push him closer toward total collapse.

Representation in Hollywood has improved on many fronts over the past decade, but that doesn’t mean that things are consistent or where they ultimately need to be. Fridging remains a common trope — a symptom of lazy writing that, due to its prevalence, has been allowed to continue. Writing something as dramatic as a character death is never easy, but when it’s done with tact and complexity — and with proper regard for the character in question — the whole story benefits. Rampantly killing off love interests rarely has the desired effect.