Rules Everyone Has To Follow On Shark Tank

At some point in the early years of their careers, it’s likely most inventors and entrepreneurs imagine themselves appearing on “Shark Tank.” The hit ABC reality investing program has become one of the most popular shows on television, featuring a wide variety of products and participants ranging from English billionaire Richard Branson to horror production icon Jason Blum. The show has cultivated such a wide fan base that companies that manage to land coveted air time in the “Tank” can expect to experience the so-called “Shark Tank” Effect, with their sales exploding in the weeks after airing often regardless of whether or not they landed a deal.

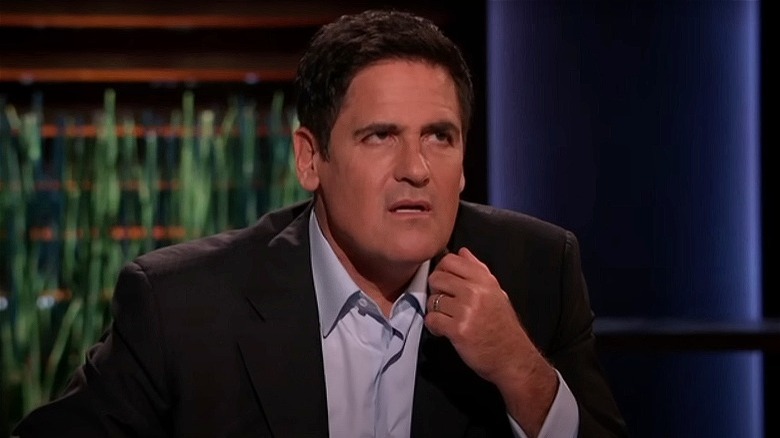

But as with any competition series, there are a litany of little known — and in some cases downright bizarre — rules that every “Shark Tank” contestant must agree to in order to pitch their product to the show’s panel of celebrity investors. For example, entrepreneurs used to have to give up equity to the show’s production company just to participate — a controversial clause that Mark Cuban successfully had retroactively removed after threatening to quit over it (another reason why we ranked him as the series’ best “Shark”). This is just one of the many restrictions that have been placed upon participants before, during, and even after their “Shark Tank” experience — and many are still around.

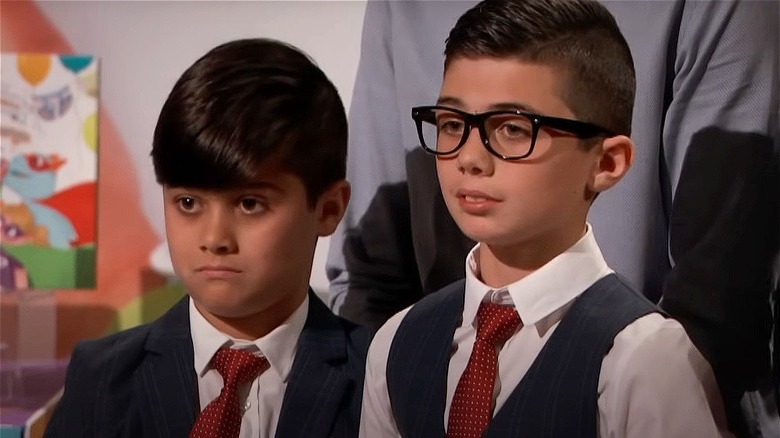

You must be 18 or older (or have a parent’s consent)

Predictably, the first barrier you’ll face to appearing on “Shark Tank” is your age. You must be 18 years of age or older in order to apply for the show, a fact which may perplex some viewers who recall the scores of young entrepreneurs that participate in the show each season. The entrepreneurs from companies Kudo Banz, Locker Board, and Wise Pocket weren’t even old enough to drive, much less sign the contracts required to be on “Shark Tank.” Yet they were indeed allowed to pitch their products and companies, and — in some cases — secure tens of thousands of dollars in investments from the panel of “Sharks.” So how is this possible?

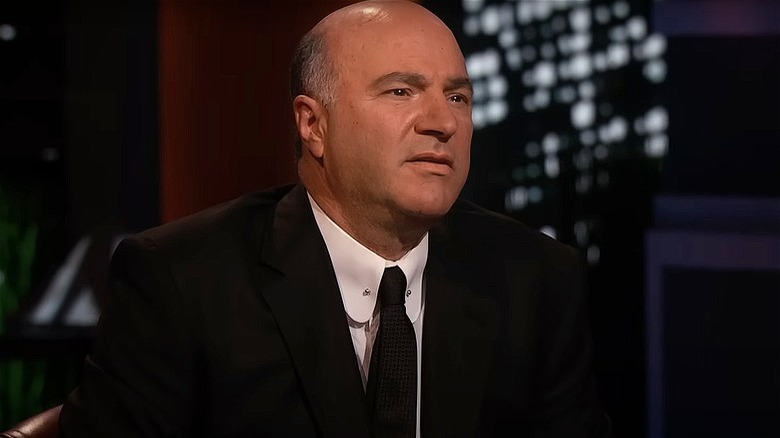

While children are more than welcome to pitch on “Shark Tank,” they must do so with the consent of a parent or legal guardian, who serves as a signatory on the contracts needed for the show. In 2014, for example, “Shark Tank” featured its youngest entrepreneur ever in six-year-old Kiowa Kavovit, who secured a $100,000 investment from Kevin “Mr. Wonderful” O’Leary in her company Boo Boo Goo.

Auditions and applications are standard

As a hopeful entrepreneur, your journey will begin not with a dramatic walk down the hallway into the “Shark Tank,” but with a lengthy application and audition process meant to determine whether or not you and your product are a good fit for the program. You can usually apply online via the show’s casting website, where you’ll find a straightforward form asking for your name, contact information, and a very basic description of what your product or company is (if able, you’re also encouraged to send in a picture as well).

Another option available to aspiring contestants are the open calls held in various major cities across the United States. There, you’ll be given the chance to present a one-minute pitch to some of the show’s casting team. While these calls do require you to have a truncated version of your presentation ready to go early in the process — and will also rely a bit more on your personality than an online form would — it does give entrepreneurs a chance to avoid getting lost in the mountain of applications the show receives before every season.

The only way to bypass the traditional audition and application process is via the direct involvement of a producer who organically came across your company and determined it would work well on “Shark Tank” — but even then, you’ll usually have to go through some kind of audition process before a formal invitation to appear is extended.

Do not contact Sharks before taping

So you’ve just received your invitation to appear on ABC’s “Shark Tank.” With this potentially life-changing news under your belt, you want to ensure you’ll make a great first impression by following all the “Sharks” on social media, sending them a quick “Thank You” note, and/or making sure they get a glimpse at your company’s stylish Instagram page — right? Wrong!

There’s probably no quicker way to get your invitation rescinded than by reaching out to a member of the “Shark Tank” before your taping. Aside from being a bit pushy, introducing yourself and your company ahead of time taints the show from both an entertainment and a competitive perspective. A big part of the show is that the investors are getting to know you for the first time, learning your life story in front of cameras aiming to capture this unique moment for audiences around the world. It’s what makes “Shark Tank” engaging as a show in the first place.

At the same time, you’re not the only contestant that needs to keep the playing field fair. The “Sharks” themselves are competing with one another to make sound investments, and any prior knowledge would give them an unfair edge over their fellow panelists. This is why every so often, when a “Shark” has formally encountered a product or company before taping (without the entrepreneur violating the rules), they’ll immediately recuse themselves and go “out” to keep the game fair for the remaining panelists.

You have to submit your pitch script to producers

Rather than pestering the “Sharks” with disqualifying DMs, entrepreneurs should be taking the time to write and/or refine their pitch for their taping. When you’ve done so, you’ll need to submit a draft of your pitch — including whatever eye-catching gimmicks you plan to include — to the producer assigned to you. As someone who both wants you to succeed and wants to create great television moments, they will then provide you with feedback and notes — and, in some cases, might even offer their own ideas for ways you can capture the attention of the “Sharks” and audiences at home.

For example, when the entrepreneurs behind the pest control product Slick Barrier prepared for “Shark Tank,” they needed a way to make bug-resistant coating less boring than it sounds. Their producer came up with the idea of having Kevin O’Leary stand on two bricks coated with Slick Barrier in a box filled with cockroaches (the “Shark” is known for using “cockroach” as a derisive nickname for obnoxious contestants). Even though the entrepreneurs were after investor Lori Greiner as a partner (and ultimately secured a $500,000 deal with her on the show), O’Leary’s stunt gave their pitch for an otherwise mundane product the sort of dramatic flare necessary to make an impact on TV.

You have to commit to a two-hour taping session

You’ve gone through the application and audition process, submitted your pitch, and assembled all the set pieces and props you’ll need (all of which you must supply yourself). Now you’re finally ready for the ultimate test of an entrepreneur’s fortitude: the “Shark Tank” pitch.

Since Season 12, “Shark Tank” has filmed at a studio in Las Vegas, Nevada. Though each episode features four pitches in under an hour, with each one lasting about 10 minutes, the actual pitch on set takes much longer. On your shooting day, you (and typically up to seven other entrepreneurs/teams) will spend one to two hours presenting your product or company to the panel. A certain amount of this extra time could very well contain the vital but non-TV-friendly aspects of negotiation necessary for you to end the day with a deal. However, because this is ultimately a television production, a lot of time is also dedicated to making sure the cameras have all the footage they need to make an engaging segment.

This could require multiple takes of certain acts (like your walk down the hallway), as well as awkward pauses to adjust lighting. Some contestants have noted that — because they still want the “Sharks” to meet you for the first time through your pitch — the first minutes of your taping can be uncomfortable, as they have to take a significant amount of time silently taping your entrance and subsequent “Shark” staredown before you can even say “Hello.”

Sharks cannot offer less money than asked

Now that your pitch can begin, you immediately need to offer the “Shark Tank” three important pieces of information — your name, the name of your company, and, most importantly, the investment you’re seeking. This initial ask can look like almost anything, from Handy Pan’s exceptionally modest $10,000 for 20% equity to Larq’s audacious $500,000 for 1% equity.

Determining your initial buy-in price is one example of how genuine competitive strategy comes into play during your “Shark Tank” pitch, as the panel is barred from making you an offer with a dollar amount below what you entered with. This means that, in Larq’s case for example, a “Shark” would have to invest a minimum of $500,000 in order to compete — which is why pitches with high starting asks face an uphill battle to land a deal on the show, regardless of the equity they’re offering.

While “Sharks” can’t lowball you on dollars, they can tweak the equity as much as they like in any direction they like. From a company like Handy Pan, they could ask for 40% of the company instead of 20% in order to get their money’s worth — or they could offer the $10,000 for just 10% in order to stay competitive with other interested “Sharks.”

A deal on the show isn’t a deal in real life

Let’s say the “Shark Tank” agrees to your dream offer of $1 million for 0.5% of your company that manufactures superior chip-clips, or something. You’re officially a millionaire now, with an imputed company valuation of $200 million, right? Wrong again!

While deals made on “Shark Tank” are real in the sense that the investors are actually interested in putting the agreed-upon amount into your business, they are not legally binding or final. In fact, investors constantly change the terms of the deal once the cameras are off — if they even go through with them at all.

Say your superior chip-clip company turns out not to have that proprietary technology or patent you bragged about in your pitch. Or maybe a more complete picture of your company’s finances reveals your sales numbers aren’t all they initially seemed to be. This information would inevitably come out during the “Shark’s” due diligence period, in which their legal team investigates your company inside and out to ensure that the deal makes real fiscal sense — a process which can often take upwards of six months to complete.

You have to undergo a psychological evaluation

Regardless of whether or not your company landed that dream deal, however, you’re bound to leave the “Shark Tank” with a lot of complicated emotions. Maybe Kevin O’Leary spent 30 minutes telling you your product was worthless, only to convince you to agree to an aggressive royalty deal; maybe you accepted an offer from Mark Cuban to buy the entirety of the company you’ve devoted your life to; or maybe that surefire dream idea you took out a second mortgage to realize just got shoved out the door without so much as a penny to show for it.

“Life-changing” doesn’t always mean “beneficial,” which is why “Shark Tank” insists that every contestant undergo a brief psychiatric evaluation before they leave the set. During the sessions, you’re asked by a professional to reflect on everything that happened during your taping and discuss your emotional state, presumably to help them determine whether your experience on the show has left you in a dangerously vulnerable place before they put you on a flight back home to reality. With real money and livelihoods on the line, it isn’t hard to imagine people potentially leaving the “Tank” with existentially disturbing states of mind.

Don’t double-cross the Sharks after making a deal

If you’re lucky enough to land a deal during your “Shark Tank” taping session, you’re well within your rights to back out at any time before closing (like, for example, if you realize during your evaluation that you don’t want to sell the entirety of your chip-clip company to Mark Cuban). What you can’t do, however, is use your “Shark Tank” deal to leverage another contract with an outside investor.

Say you go to one of Cuban’s billionaire pals with what you believe to be an intriguing bit of insider info — one of the world’s most respected investors believes your company will make him so much money that he went all-in. Now, the deal isn’t officially closed, so if his pal has a better offer, of course you’d be willing to consider it. That is, if you want to be on the receiving end of a scorned billionaire’s legal team. However, assuming you still have equity to give up, you’re likely safe to continue seeking investment at the valuation your “Shark” invested at.

Similarly, you might be tempted to renegotiate your valuation with Cuban after that “Shark Tank” effect hits and your sales shoot through the roof. While you can technically attempt to alter the terms of the deal just as they can, attempting to leverage the opportunity they gave you to squeeze them for more money probably won’t bode well for an ongoing partnership.

You can’t spoil the result of your appearance

In the months after you’ve made your “Shark Tank” deal, while you wait for your new finned financier to close that multi-million-dollar chip-clip deal you’ve been dreaming of, you’re also waiting for something else almost just as important — an email from producers letting you know that your segment has been selected to air.

About 80% of “Shark Tank” pitches ultimately make it to the show, with entrepreneurs getting a heads-up just a few weeks before airing that they’ve been chosen. Scott Jordan (who pitched his product SCOTTeVEST all the way back in Season 3) revealed that he received two notifications at the time — one that he had been chosen at the end of the filming period and another revealing his airdate, two weeks prior to the night in question. This is to give entrepreneurs plenty of time to stock up on inventory and, in some cases, develop specific marketing and public relations strategies for the weeks after their small-screen debut.

While you aren’t allowed to reveal whether or not you made a deal on your episode prior to it airing, you are allowed to let people know that you’ll be featured so they can tune in to see your pitch (you’re ultimately advertising the show to your customers, after all). After it airs, you’re officially free to present yourself as a “Shark Tank” company — but you’re still bound by your contract in at least one peculiar way.

You can’t run for public office

Strangely enough, you cannot be running for political office when you appear on “Shark Tank,” and you must agree not to do so for at least one year after your episode airs. It’s truly terrible news for everyone hoping to go from chip-clip salesperson to presidential candidate via the “Tank.”

As odd as this restriction may seem, it does make sense in terms of keeping the show as pure as possible. From ABC’s perspective, it protects their brand to prevent a contestant on “Shark Tank” from turning around and becoming a politician who’s immediately controversial among half the voting population. But more than that, this rule prevents those running for office or planning to run in the near future from misusing their “Shark Tank” appearance as a launching pad for a campaign.

Hypothetically, a particularly cynical and confident candidate could time their moves precisely so that their episode — which will be seen by millions of Americans — airs around the same time that they announce their candidacy. In smaller races, this could allow something as silly as “Shark Tank” to have an actual effect on the government.

You can’t pitch the same product twice

The reality is that only about half of all participants leave the “Shark Tank” with any sort of “deal” — and only half of that half will actually end up closing said deal. It’s a high-stakes game where the odds of true success are worse than the flip of a coin — and there are absolutely no do-overs.

Once you pitch a product in the “Shark Tank,” you are not allowed to apply with that same product and pitch ever again, not even if you leave without a deal. That said, there are some fairly large loopholes in this rule that entrepreneurs have been able to exploit. For example, it’s entirely possible for the same entrepreneur that left the “Tank” without a deal to return with a slight variation on the product or after a significant update to the company.

Jim Martins turned down Kevin O’Leary’s offer of $600,000 for 51% of Copa Di Vino, then returned a season later after doing $5 million in sales in less than a year — only to walk away without a deal for a second time. Alternatively, the water sports company Kymera returned to the “Tank” after developing their brand over the course of two years, and went from no deal to a $500,000 deal with Robert Herjavec. So even if everyone passes on your chip-clips the first time around, enough perseverance could earn you one more swim in the “Shark Tank.”