Before there was Tom Ripley, there was Bruno Antony.

The Big Picture

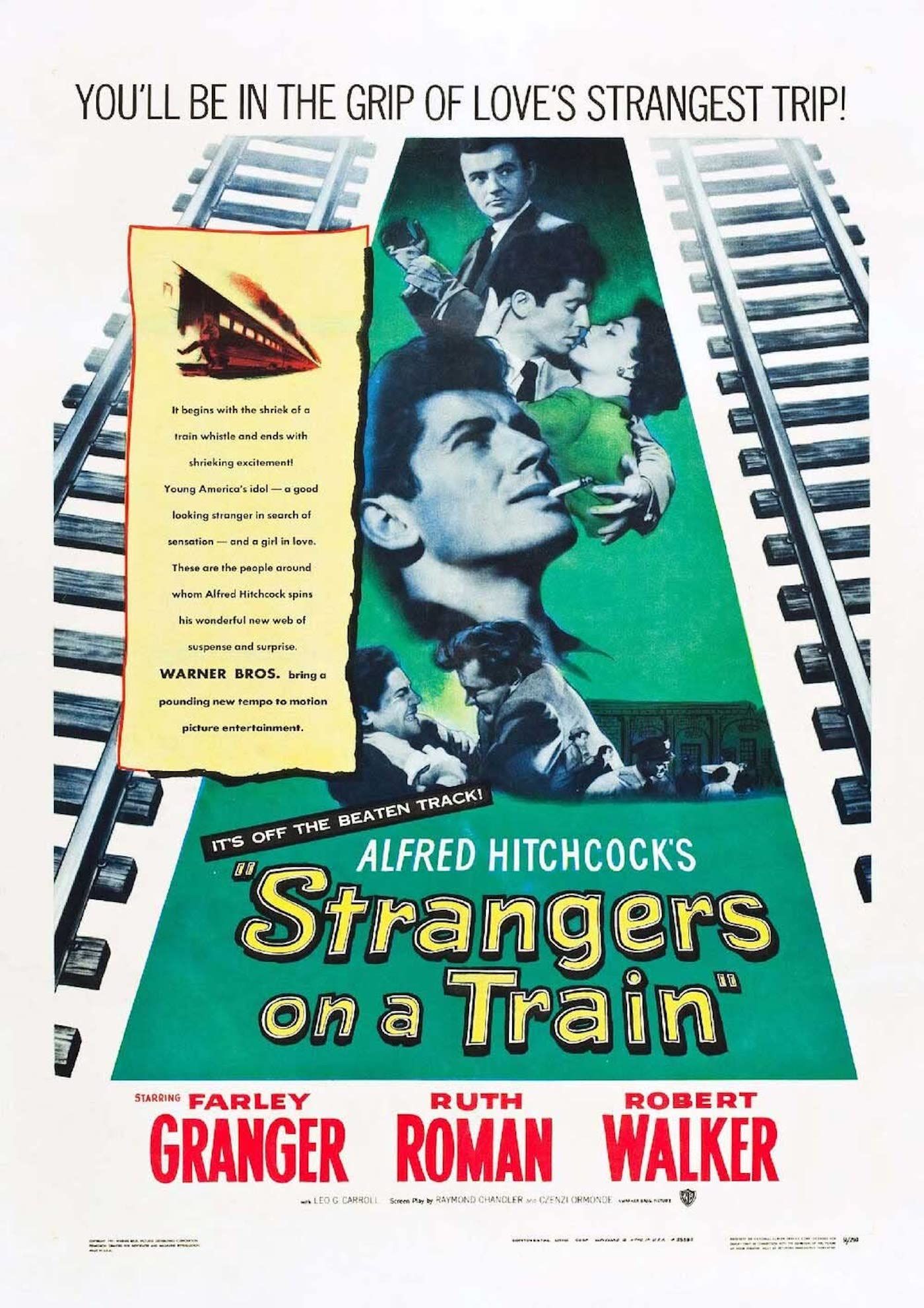

- Hitchcock’s film “Strangers on a Train” excellently portrays a high-stakes game of murder and manipulation between two intriguing characters.

- The film serves as a powerful queer metaphor, shedding light on issues of acceptance, ostracization, and the consequences of discrimination in society.

- Hitchcock’s daring casting choices and subtle nuances deepen the film’s impact, making it a timeless classic with undeniable queer undertones.

Author Patricia Highsmith has been responsible for many of our most beloved works of film and TV. After Saltburn re-catapulted The Talented Mr. Ripley into the cultural conversation, the new TV adaptation of her seminal book series has just come out on Netflix. There’s also 2015’s Carol, the immediate queer classic that was adapted from her second book, The Price of Salt. But it wasn’t just posthumously that Highsmith achieved all this success onscreen – her very first novel, Strangers on a Train, was adapted by none other than the Master of Suspense Alfred Hitchcock into one of his perennial thriller classics merely a year after its publication.

Even though Hitchcock heavily altered Highsmith’s original plot, a close analysis of Strangers on a Train reveals many similarities to Ripley. Both works are about suave killers who socialize their way into the settings of their pawns. Both pieces are fascinated with their obviously queer-coded villains and function as allegories for the oppressive closet. But it is Hitchcock who takes Highsmith’s signature themes to delicious, pulse-pounding heights, casting a tall influence over the 1999 Ripley film’s director Anthony Minghella, and the Netflix series’ creator Steve Zaillian.

Strangers on a Train

A psychopathic man tries to forcibly persuade a tennis star to agree to his theory that two strangers can get away with murder by submitting to his plan to kill the other’s most-hated person.

- Release Date

- June 27, 1951

- Director

- Alfred Hitchcock

- Cast

- Farley Granger , Ruth Roman , Robert Walker , Leo G. Carroll , Patricia Hitchcock , Kasey Rogers

- Runtime

- 101

- Main Genre

- Crime

- Writers

- Raymond Chandler , Czenzi Ormonde , Whitfield Cook , Patricia Highsmith , Ben Hecht

- Tagline

- It starts with a shriek of a train whistle…and ends with shrieking excitement.

What Is ‘Strangers on a Train’ About?

But first, a recap of Strangers on a Train: in one of Hitchcock’s most famous, straight-to-the-point openings, Guy (Farley Granger) and Bruno (Robert Walker) meet on a train. Guy is a famous tennis player, and Bruno a major fanboy. From gossip columns, the fan knows Guy wishes to divorce his unfaithful, uncooperative wife Miriam (Kasey Rogers) and marry his new girlfriend Anne (Ruth Roman), the daughter of a senator. Perhaps mischievously, Bruno suggests they “swap murders” – Bruno will murder Miriam, while Guy will murder Bruno’s disapproving father. Slightly alarmed, Guy uses his social skills to brush off Bruno’s advances, but little does he know he has been caught in the web of a psychopathic killer. Bruno will pursue his plan at all costs, even at the expense of other human lives.

Like many other classics by Hitchcock, the 1951 film was not received the best upon initial release. However, Hitchcock was coming out of a post-WWII slump, and the film nonetheless revitalized him into the 1950s, inarguably his most successful decade, dotted with classics like Rear Window, Vertigo, and North by Northwest. Modern opinion has solidified Strangers on a Train as one of the major touchstones in Hitchcock’s filmography, with many titles inspired by it and even an attempt to remake it by David Fincher. But the Hitchcock flair still stands unparalleled – while Minghella’s Ripley kills as bluntly as a blow to the head, the shadow of Hitchcock’s Bruno looms over his prey. A late chase on a carousel is one of the most berserk, frenetic things you’ll ever see, and even though tennis is merely a backdrop in this film, Hitchcock has somehow also made his film into one of the greatest tennis films of all time, by tensely cutting the sport into the plot.

Like ‘Ripley,’ ‘Strangers on a Train’ Is a Brilliant Gay Metaphor

The most important element that Hitchcock didn’t hesitate to highlight is the giant gay metaphor hanging above the film. Queer-coded villains aren’t new to Hitchcock – or even other films of that era – Rebecca‘s Mrs. Danvers is obsessed with the eponymous character while Rope‘s leading men are pretty obviously a gay couple living together. What particularly substantiates Strangers on a Train‘s claim is that Bruno is heavily ostracized and cast out by his father. While his father may have good reason to question his murderous son, the language he uses behind Bruno’s back painfully evokes the hateful prejudices flung at queer people over time, such as “he should be sent someplace for treatment” and “I’m going to have that boy … put under restraint.” (It must be noted that the “boy” is 32-year-old Robert Walker.) In this early scene, Hitchcock establishes the murderous Bruno as a somewhat sympathetic character, not given a chance by his father and presumably having grown up in an unloving environment. That echoes the harsh experience so many gay people face even to this day. Stereotypes of his mother’s loving care, a few flamboyant mannerisms, and intricately patterned, silk costumes make it transparent that this character is meant to be gay – Hitchcock and Walker knew what they were doing.

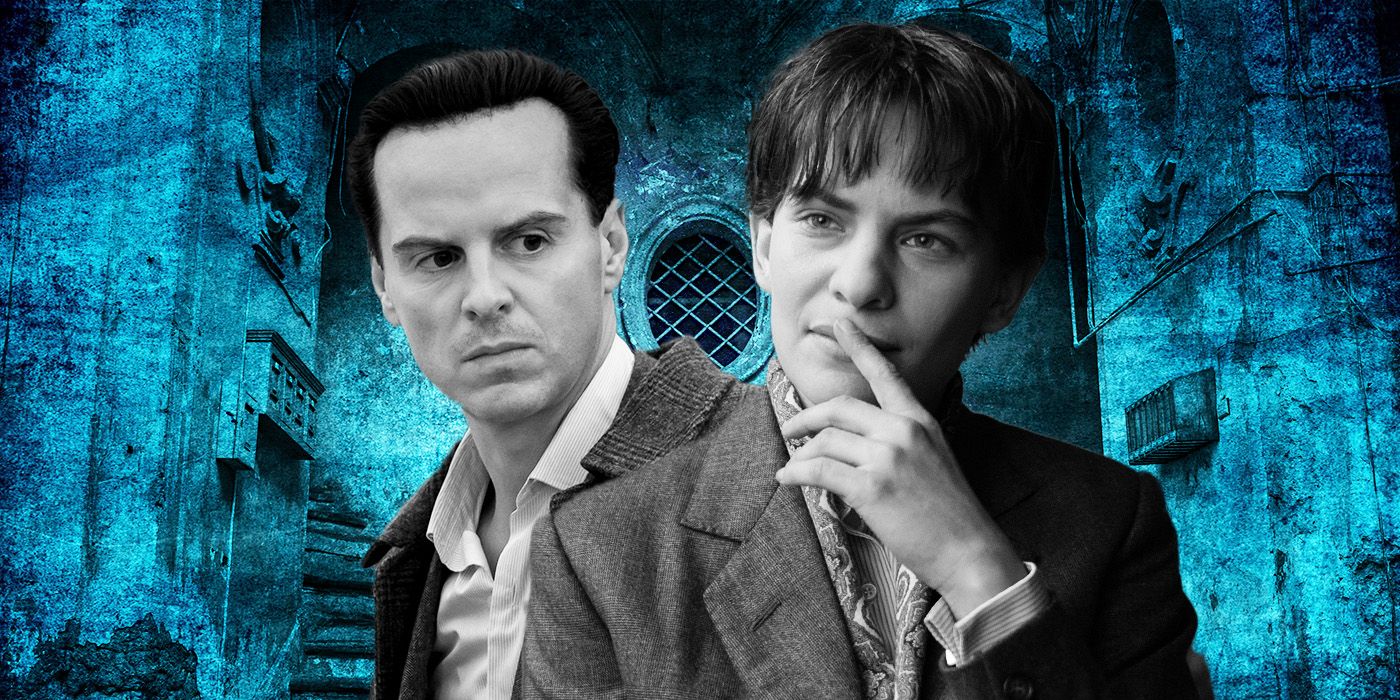

Netflix’s ‘Ripley’ Really Takes Its Time — And That’s Why It’s So Damn Good

Slow and steady definitely wins the race.

One must be careful with drawing this comparison though – just because you’re gay, it doesn’t mean you automatically go around murdering people. But by hypothesizing his father’s rejection as the source of Bruno’s evil, Hitchcock implies the dark and potentially disastrous consequences of homophobic discrimination. Only appearing briefly, Bruno’s father is more a figure than a character in the film, and he effectively represents the patriarchy that dominates and runs society? 1951 was, of course, the height of McCarthyism, which included not only the Red Scare but also the lesser-known Lavender Scare. Any government officials suspected of queerness were brutally interrogated and stripped of their careers. And where does Strangers on a Train take place? You guessed it, Washington D.C., where Hitchcock shot national landmarks like the Jefferson Memorial and Capitol Hill looming over our characters. Hitchcock never set another film in the capital. This pipeline from repression to crime is the same basic plot in Ripley as well.

‘Strangers on a Train’ is Almost a Queer Romance

The case of Bruno is pretty open-and-shut; it is Guy’s that is interesting. Is Guy a homosexual as well? Hitchcock has gone to such lengths to show Guy as straight that the effect is almost ironic. Guy is settling his affairs between two women, and he appears almost obnoxiously hand-in-hand with Anne. He is dressed in the much more typically masculine prep aesthetic. But there’s more to him that suggests a potential gay undercurrent. Is his high-profile decision to woo a senator’s daughter a ruse to mask his true sexuality? (That is literally the exact same plot of last year’s Lavender Scare series, Fellow Travelers.) His constant PDA almost looks like an overcompensation for whatever went wrong with his previous marriage.

If one approaches Strangers on a Train as a courtship between Guy and Bruno, the entire film changes. The titular encounter on a train resembles cruising, and Hitchcock is careful to highlight the physical contact between the two men. For half of the film, Guy hides his familiarity with Bruno from Anne, like a closeted gay man hiding his affairs from his wife. Guy is shown to be somewhat affectionate for Bruno in the end, begging for Bruno’s life and calling him a “very clever fellow.” Bruno represents the repressed gay desire in Guy, following him around and threatening to emerge. With Guy and Anne cheekily reunited on a train, the heteronormative, Code-abiding ending of the film suggests that all will be well once the desire is extinguished. However, Hitchcock biographer Charlotte Chandler attests in It’s Only a Movie: Alfred Hitchcock, A Personal Biography that those studio-mandated scenes were not Hitchcock’s intentions. Instead, Hitchcock wanted to end with the heartfelt “clever fellow” scene – the two men looking into each other’s eyes. That revelation completely changes the meaning of the film, showing it is the homosocial recognition between the two men that is Hitchcock’s focus. This tradition continued on into many other closeted films, such as The Talented Mr. Ripley, Saltburn, and John Woo’s famously homoerotic heroic bloodshed films.

Hitchcock’s Vision Remains Unparalleled and Inspires Stories to This Day

Hitchcock’s greatest stroke of genius in this film is the casting. With these characterizations in mind, most directors would cast a more conventionally masculine actor in the role of the star athlete and a more effeminate actor as the gay-coded killer. Not Hitchcock, who imaginatively cast Farley Granger as Guy and Robert Walker as Bruno. Granger was famously closeted, had already played one of the thinly veiled gay lovers in Rope, and wore softer, delicate features. Walker, on the other hand, was a much more traditionally brooding man (he was also a Republican Mormon in real life). By subverting these stereotypes, Hitchcock deepened his film tenfold. He made the possibility of romantic tension between the two men much more palpable and Bruno’s obsession with Guy much less stereotypically creepy. This is a courageous, brilliant move that even directors today can’t pull off. With more openness about repression leading to murder, one can see the Ripley media as natural successors to Hitchcock’s films, in a world without the puritanical Hays Code. But even with restraints in place, Hitchcock still somehow made a gay classic beloved by queer cinema fans worldwide. And if you don’t see the gay implication, the film remains a fine crime thriller.

Strangers on a Train is available to rent in the U.S. on Amazon Prime Video.

RENT ON AMAZON

This article was originally published on collider.com