Eddie Murphy partially credits a night out with Robin Williams and John Belushi in the 1980s for helping him realize he “wasn’t interested” in drugs — something he sees as a gift from up above.

“I remember I was 19, I went to the Blues Bar. It was me, [John] Belushi and Robin Williams. They start doing coke, and I was like, ‘No, I’m cool,’” Murphy, 63, shared with David Marchese during the upcoming episode of the New York Times’ “The Interview” podcast. “I wasn’t taking some moral stance. I just wasn’t interested in it. To not have the desire or the curiosity, I’d say that’s providence. God was looking over me in that moment. When you get famous really young, especially a Black artist, it’s like living in a minefield. Any moment something could happen that can undo everything.”

Belushi died of a heroin overdose at the age of 33 in 1982. Williams, meanwhile, died by suicide in 2014 after a lifelong battle with depression. Murphy reflected on the tragic endings of Williams, Belushi and other legendary stars, like Elvis, Michael Jackson and Prince, calling them “cautionary tales” for his own life.

“I don’t drink. I smoked a joint for the first time when I was 30 years old,” he shared. “The extent of drugs is some weed.”

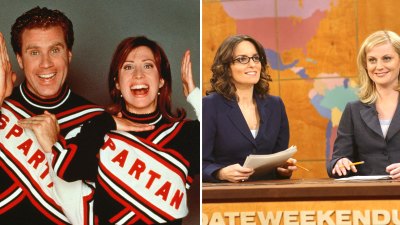

Saturday Night Live was on the verge of cancellation when Murphy joined the cast in 1980. His characters, like Gumby and his Mr. Rogers parody, Mr. Robinson, helped skyrocket the show to late-night success. His career quickly reached new heights with movies like Beverly Hills Cop and 48 Hrs. While speaking to the NYT, the comedian said he knew from a young age he would eventually become famous, but in hindsight, he didn’t always appreciate his level of success once he found it.

“I started at maybe around 13, 14, saying that I was going to be famous,” he recalled. “I’d tell my mother, ‘When I’m famous. …’ So when I got famous, it was like, See, I told you.’ I was having these famous people that I grew up watching on television wanting to have a meal with me. After 48 Hrs, Marlon Brando calls my agent and wants to meet me. Now I look back and go, ‘Wow, that’s crazy, the greatest actor of all time wants to have dinner with you!’ But back then I just thought, ‘Well, that’s the way it is — you make a movie, and Marlon Brando calls.’”

Keep scrolling for more from Murphy’s upcoming interview with the New York Times:

New York Times: You said you took [your fame] for granted, which, that’s crazy.

Eddie Murphy: I started at maybe around 13, 14, saying that I was going to be famous. I’d tell my mother, “When I’m famous. …” So when I got famous, it was like, “See, I told you.” I was having these famous people that I grew up watching on television wanting to have a meal with me. After 48 Hrs. Marlon Brando calls my agent and wants to meet me. Now I look back and go, “Wow, that’s crazy: The greatest actor of all time wants to have dinner with you!” But back then I just thought, Well, that’s the way it is: You make a movie, and Marlon Brando calls.

NYT: Is [standup comedy] appealing to you?

Murphy: Here’s a good analogy. It’s like somebody that was in the military. They were on the front line in Vietnam, and they got all these medals because they did all this amazing stuff. Then they moved up and became a general. So it’s like going to the general and saying: “Hey, you ever think about going back to the front line? You want to have bullets whiz past your ear again?” No!

NYT: Elvis, Michael Jackson, these guys achieved the apex of fame. Prince is another like that. And there was a period when you were at that level.

Murphy: Yeah, I went through all of that.

NYT: Those guys all came to tragic ends. Do you understand the pitfalls that present themselves at that level of fame?

Murphy: Those guys are all cautionary tales for me. I don’t drink. I smoked a joint for the first time when I was 30 years old — the extent of drugs is some weed. I remember I was 19, I went to the Blues Bar. It was me, [John] Belushi and Robin Williams. They start doing coke, and I was like, “No, I’m cool.” I wasn’t taking some moral stance. I just wasn’t interested in it. To not have the desire or the curiosity, I’d say that’s providence. God was looking over me in that moment. When you get famous really young, especially a Black artist, it’s like living in a minefield. Any moment something could happen that can undo everything.

NYT: Do you feel as if you’ve taken cheap shots from the press over the years?

Murphy: Back in the old days, they used to be relentless on me, and a lot of it was racist stuff. It was the ’80s and just a whole different world. … When David Spade said that [expletive] about my career on [Saturday Night Live] it was like: “Yo, it’s in-house! I’m one of the family, and you’re [expletive] with me like that?” It hurt my feelings like that, yeah.

He showed a picture of me, and he said, “Hey, everybody, catch a falling star.” It was like: Wait, hold on. This is Saturday Night Live. I’m the biggest thing that ever came off that show. The show would have been off the air if I didn’t go back on the show, and now you got somebody from the cast making a crack about my career? And I know that he can’t just say that. A joke has to go through these channels. So the producers thought it was OK to say that. And all the people that have been on that show, you’ve never heard nobody make no joke about anybody’s career. Most people that get off that show, they don’t go on and have these amazing careers. It was personal. It was like, “Yo, how could you do that?” My career? Really? A joke about my career? So I thought that was a cheap shot. And it was kind of, I thought — I felt it was racist.

NYT: I had also asked you a question about how you think about your relationship with your audience. You said you approach it from the perspective of, you’re going to make what you think is funny, and hopefully, the audience likes it. You also said that you’re looking to do projects that you’re confident will succeed. But don’t you have to think about the audience’s needs in order to have a sense if something is going to work or not.

Murphy: How could you think about the audience’s needs? Eight billion people on the planet. They don’t know — that’s a better way of putting it: The audience has no clue what’s funny. You’ve got to show them what’s funny. They don’t know. And if something is funny to me — I’ve never had anything that made me laugh that then when I said it to an audience, the audience just sat there and looked at me. If I think it’s funny, it’s always funny.

NYT: Do you understand what you mean to comedians like Kevin Hart and Dave Chappelle and Chris Rock and Chris Tucker?

Murphy: Well, I didn’t lay down a path. They took their own path. The comic used to be the sidekick, the comic was the opening act, and I changed it to where the comic can be the main attraction. They thought of comics one way, and it was like, no, a comic could sell out the arena, and a comic could be in hundred-million-dollar movies. All of that changed. And with Black actors, it was, like, the Black guy could be the star of the movie, and it doesn’t have to be a Black exploitation movie. It could be a movie that’s accessible to everyone all around the world.

NYT: One of the other things that stuck with me from our first conversation was that you described getting to do what you do for a living as a blessing. I was thinking about that in the context of how you also said that you knew you were going to be famous. When did you stop taking success for granted?

Murphy: I knew it was a blessing from the beginning.

NYT: So you didn’t take it for granted?

Murphy: I took how fast everything was moving for granted. Like, I guess this happens for everybody; this is what happens when you get famous. So I took all of that for granted but I was never like, “I’m the [expletive].” There’s no higher blessing: You make people laugh, that’s more than anything. That’s more than making them dance, making them feel drama. To look around and see that all the good things that came in my life all came from making somebody laugh? That’s a beautiful feeling, man.