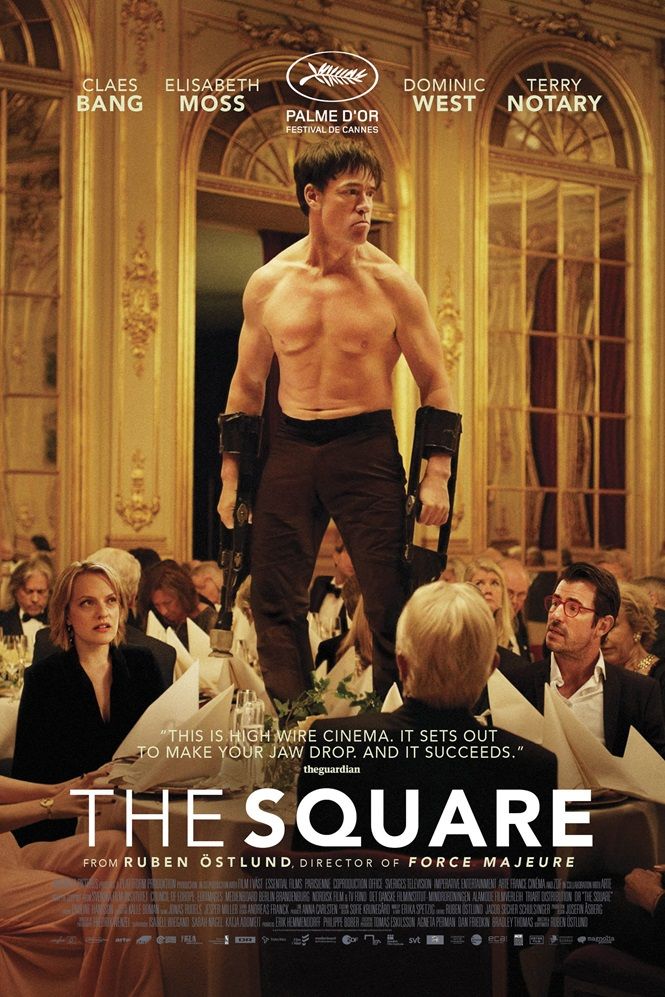

Östlund’s unrelenting satire starred Elisabeth Moss, Claes Bang, Terry Notary, and Dominic West.

The Big Picture

-

Triangle of Sadness

was a breakout film that challenged mainstream expectations with cringe-inducing moments and comedic depth. - Ruben Östlund’s

The Square

also mocks societal hypocrisies, selfishness, and our inability to address uncomfortable truths. -

The Square

uses irreverent humor to explore the idea that true collaboration and righteousness often emerge when all other options are exhausted.

When Triangle of Sadness stormed its way onto the mainstream stage, breaking free of its arthouse roots to achieve Academy Award recognition, it caught everyone offguard. Coming at the tail end of a wave of films all espousing the “eat the rich” philosophy, it stood out from the crowd due to its commitment to cringe-inducing set pieces and its commitment to taking broad comedic sensibilities and packaging them in the veneer of a more serious-minded prestige film. It was a film that found space for the highs of explosive projectile vomiting out of a Monty Python skit and the lows of all the characters we’ve grown attached to revealing themselves as selfish and spiteful gremlins, if the opportunity presented itself. This juxtaposition is something its writer-director Ruben Östlund is a particular master at, as exemplified in his previous film, The Square, which sought to skewer the world of high class art, but still remains focused on the concepts of social privilege and the self-serving nature of humanity.

The Square (2017)

A prestigious Stockholm museum’s chief art curator finds himself in times of both professional and personal crisis as he attempts to set up a controversial new exhibit.

- Release Date

- September 29, 2017

- Actors

- Claes Bang, Elisabeth Moss, Terry Notary, Dominic West

- Director

- Ruben Östlund

- Run Time

- 151 mins

- Studio

- Magnolia Pictures

What Is ‘The Square’ About?

Christian (Claes Bang) is a successful curator of a contemporary art museum, and he’s gearing up to unveil his next big show. It will be called “The Square,” and it will be just a square on the ground, with a plaque next to it that preaches altruism and humankind’s responsibility towards each other. This is such an obvious low-hanging fruit that the plaque will become increasingly mocking, as Christian will go through a series of embarrassments, mistakes, and bad decisions that will reveal how out of touch he is with his alleged principles. His cell phone and wallet get stolen, and his cell phone tracker leads him to an apartment building he’s never seen, and he leaves a letter in every single mailbox in the hopes that one of them is the culprit. He has an interview with an American journalist named Anne (Elisabeth Moss), which leads to a poorly chosen one-night stand that reveals his callousness towards women. The advertising agency that the museum hired to promote “The Square” reveal themselves to be hilariously out of touch with how to reach the public by suggesting a viral video of a poor child blowing up inside the Square, which Christian approved of only because he wasn’t really paying attention to the video in the first place. He also eventually gets a surprise visit from his two daughters, who he seems mostly irritated and dismissive of.

Over and over, he’s revealed to be a massive hypocrite whose sense of righteousness and morality only come from his sense of self-preservation and are motivated by his feeling that his life either is or needs to be in a good place. For instance, one small subplot is him encountering a homeless woman at a sandwich shop. She asks for money, and he says he has no paper money, but offers to buy her a sandwich. She asks for a ciabatta with no onions, and he buys her a ciabatta, but forgets the no onions and barely thinks about her once he leaves. Later, after he retrieves his wallet to find it’s still full of cash, he excitedly goes and gives her at least three bills worth of his own money. In this one episode, we see how Christian must already be in a promising position in order to extend himself to others. If the tables turn against him, his selfishness takes over and everything must be filtered through how it helps him.

‘The Square’ Mocks Our Inability to Get Out of Our Own Way

Christian isn’t alone when it comes to this falling back on his baser needs, as the film is peppered with scenes of people allowing themselves to become prisoners of the moment and unwilling to try and make any meaningful change. The two most infamous scenes of the film paint this truth in brutally blunt strokes, aided by a sharp understanding of how crowd psychology takes over. In one scene, an artist named Julian (Dominic West) is being interviewed on stage, and a member of the audience has a severe case of Tourette’s, constantly hurling inappropriate threats at the artist and his interviewer. The artist and interviewer try to politely accept him, due to his condition, while others passively complain about his presence, but still, no one actually does anything meaningful about the situation. In a later scene, a major dinner event for the museum’s benefactors has a show in which a performer named Oleg (Terry Notary) demonstrates his human ape act, giving the rich suits an interactive experience they couldn’t have seen coming. What starts out as a pleasant distraction quickly grows more disturbing, as Oleg loses himself in the role and starts chasing people down and jumping on tables, with the guests eventually interfering only when he reached the point of almost assaulting a woman. While one scenario is effectively a sketch comedy bit and the other is an increasingly harrowing nightmare, both scenes work because they’re firing shots at every person involved equally. Plus, they underline the notion that, on average, human beings aren’t willing to stand up for others unless things reach a mandatory point or there’s actual skin in the game for their own self-image.

Woody Harrelson’s ‘Triangle of Sadness’ Performance Shows the Duality of Liberalism

Woody Harrelson’s specificity and sense for his character’s inner turmoil provides a nuanced examination of the guilt-ridden American liberal.

Bringing it back to Christian, his continued meetings with Anne show how much this idea is single-handedly ruining his life. Every time they meet up, something goes horribly awry, usually due to his own narcissism or the art world around him being too fixated on its own proclivities to make accommodations for the human experience. There’s a scene where, after they have sex, he refuses to give her his used condom to throw away, because he’s convinced she’s going to secretly do something with it. It’s so flagrant that she even calls out his own narcissism, in the best cringe comedy kind of way. That flavor of comedy gets boosted in a later scene where they have an argument over their sexual encounter, which he can barely admit to. The entire duration of the fight, a piece of art that’s just a giant mountain of metal deck chairs glued together is being ever so slowly pushed along the hard floor by a worker, which makes the worst scraping noise every three seconds. You can tell that both Christian and Anne can hear it and are trying so hard to ignore it, and it’s a wicked serving of karmic justice for both of their prior actions, reminding you that no one is safe from criticism or the consequences of their selfishness in Östlund’s world.

‘The Square’ Uses Irreverence to Preach Sincere Collaboration

Fight Club espoused the philosophy that it’s once you lose everything that you’re free to do anything. The Square seeks to modulate that idea, changing it to: it’s only when you’ve run out of every last option that some people will finally do the right thing. What starts out as just an event to kick the plot off becomes the defining moment of Christian’s arc, as his leaving accusatory letters at the apartment complex comes around to blow up in his face. A small Arab boy angrily pursues Christian to his building, insisting that his parents now see him as a thief due to the letter, despite him being innocent. Christian is indignant and refuses to acknowledge he did anything wrong, to the point that he pushes the boy down his building’s stairs, and refuses to help him, even as he hears the boy yelling for help. It isn’t until the guilt gnaws at him enough, and he realizes the boy is gone, that he posts a video apology and attempts to send it to the boy and his family. As a final cherry on top, when he goes to formally apologize to the family, it turns out they’ve moved away. By the time he finally bothered to do the right thing, the opportunity literally left him behind.

But perhaps all isn’t lost for Christian, by his relatively low standard. Östlund might have fun poking fun at the concept of good taste, but he’s not abjectly cruel. He does have some belief in the notion that people can evolve or grow to an extent that is plausible for each person’s individual makeup. The film ends with Christian formally stepping down from his curator position over backlash to the viral video, and trying to reconnect more with his daughters. They’re cheerleaders for their school, and he goes to one of their performances, where they partake in an elaborate and perfectly executed routine, all done on a stage in the shape of…a square. Christian seemed to believe he was going to do something novel by presenting “The Square” in his museum, attempting to preach a hollow message of solidarity and community. Similar to how the plaque served as a mockery of his intentions, but the cheerleading performance serves as a living demonstration of what he wanted to achieve, life once again finding a way to thumb its nose at him.

The Square is currently available to stream on on Max in the U.S.

This article was originally published on collider.com